Algorithms Are Not Your Friends. Here's How to Fight Back.

In her book, Weapons of Math Destruction, Cathy O'Neil investigates the dangers of abusing algorithms for corporate and political gain.

Steven Puri

Math Distraction

In 2015, Facebook researcher Solomon Messing altered the news feeds of two million users to see if the platform could affect political engagement. The now-famous (some would call it infamous) project increased voter participation by three percent in the group that was fed more hard news. The other group, which saw an uptick in cat videos and birthday photos, experienced no change in voting patterns.

Facebook’s news feed is not benign. NY Times reporter Kevin Roose regularly reports the top-performing Facebook links. The top nine news sources on July 21 were from conservative outlets, including four posts by Ben Shapiro alone. On some days, all 10 are from similar outlets. Facebook is a non-specific amplifier, though as precedent shows, it skews Right.

The problem isn’t your political party. The problem, argues data scientist Cathy O’Neil in her book, Weapons of Math Destruction, is the algorithm itself. O’Neil points out that a majority of people still believe you only see your friend’s posts when you scroll, instead of the reality, which is that Facebook’s AI tailors content to confirm your pre-existing beliefs so you’ll continue to scroll. The more attention you give, the more ads you see, the more Facebook makes in advertising revenue.

Unlike a traditional news outlet, you can spend all of your time on Facebook (and other social media sites) without running into stories that conflict with your biases. A three percent increase might appear to be a positive—more voter participation!—but what’s left out of the story is how the platform sways the electorate by feeding particular stories.

This was confirmed in a definitely infamous 2012 Facebook experiment in which 680,000 users were fed either positive or negative content. They were, unsurprisingly, swayed in the direction the algorithm dictated.

Sometimes, math really isn’t hard. But it sure can be distracting.

On Task

A 2015 study at the University of California Irvine found that it takes 23 minutes and 15 seconds to get back on track after being interrupted. Interruptions are unavoidable when notifications are turned on. Factor in those seemingly little social media dopamine rewards and it’s likely that many people never enter Flow States while at work.

Hungarian-American psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi began studying what he would term "Flow" in 1975. After studying the phenomenon for over a decade, he detailed the factors necessary for achieving this mental state, which is characterized by complete absorption in a task that results in a transformation of your sense of time.

Csikszentmihalyi understands that you have to engage in tasks you have a chance of completing. The Irvine study found that 82 percent of workers returned to their interrupted work the same day, though the time it took to complete their work was longer.

Other conditions for Flow include an ability to concentrate solely on the task in front of you and having total control over your actions. Deep focus and feeling in control allow your mind to enter this timeless state.

By the end of your day, you feel more satisfied and happy.

This is exactly the feeling the algorithms are designed to stop.

Training for Flow

People who train to get into Flow States reach them more often.

Flow is not a mystical sensation that arises spontaneously. It requires dedication and perseverance. As Csikszentmihalyi phrases it,

Optimal experience is thus something we can make happen.

O’Neil advocates for a sort of Hippocratic oath for data scientists as a way to consider ethics in equations. The distraction technologies created by social media companies make us less productive in order to increase revenue. Google might offer employees mindfulness training to increase their productivity, yet their product accomplishes the opposite: it keeps us searching through a world of information instead of staying focused on the task at hand.

While algorithms are controlled by AI, humans write the algorithms. As O’Neil writes, "A statistical engine can continue spinning out faulty and damaging analysis while never learning from its mistakes."

That means we have to learn from our mistakes and demand that the engineers behind those algorithms write better code.

Unfortunately, that’s going to take a lot of work. The algorithms work—for social media companies. As long as profits roll in, there’s no incentivization to create an ethical AI. The change is up to us.

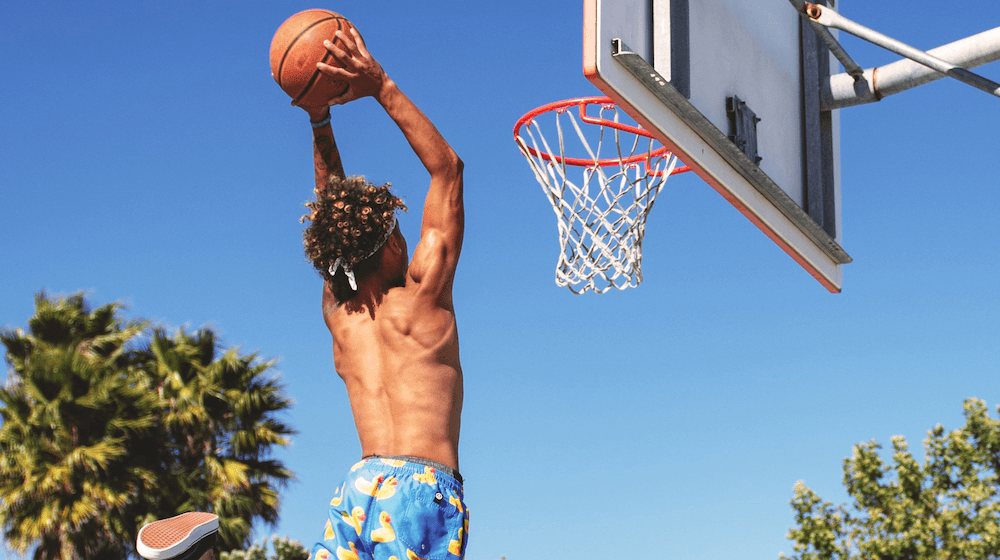

Then again, Flow States always take work, regardless of your environment. The magic of soaring over defenders like Michael Jordan, the endless hours he spent training to get “in the zone,” the feeling like you’ve transcended space and time when completely immersed in the present—a moment in which anything is possible—all contribute to the beauty of Flow.

If the algorithms aren’t going to support this quest, turn your devices off. Shut down notifications, remove apps from your phone, whatever it takes. The empty calories and stressful consequences of a quick dopamine hit can never compare to the sustained focus of a Flow State.